REVIEWER: Wendy Donawa is grateful to live on the unceded territory of the Songhees and Esquimalt peoples, and to see the Salish Sea and the Sooke Hills from the window over her desk. Our Bodies’ Unanswered Questions is her second collection.

Poet Wendy Donawa

unpacking the poem:

Regional reviewers focus on regional poems

Reviewer Wendy Donawa unpacks a different poem every month. She examines the poem in a way she hopes is helpful for readers and other poets to understand how craft works in a particular poem, for a particular effect.

September 2022: Linda K. Thompson

Bring this Stone to the Grave

Come up through the fields.

It is spring here now, and the winds are sweeping

down from the north along the valley, rattling the birches,

drying the pastures and last fall’s potato fields.

The fences are crumpled by another hard winter,

but the days are stretching out, the sun inching its way

to the place where it dips behind Camelback in June and July.

Orioles and waxwings are flying through the nights,

warblers remembering the mountain ash and linden

Mother planted all those years ago.

Bring this stone.

You are alone and its heft will be company.

Smooth as one of Father’s old Viyellas,

pale as the silt on the sandbar where the Herefords bent to drink,

and we played in the long summers.

Still, the sun across the cottonwoods that line the Lilloooet

will nearly break your heart.

Poet Linda K. Thompson and friend.

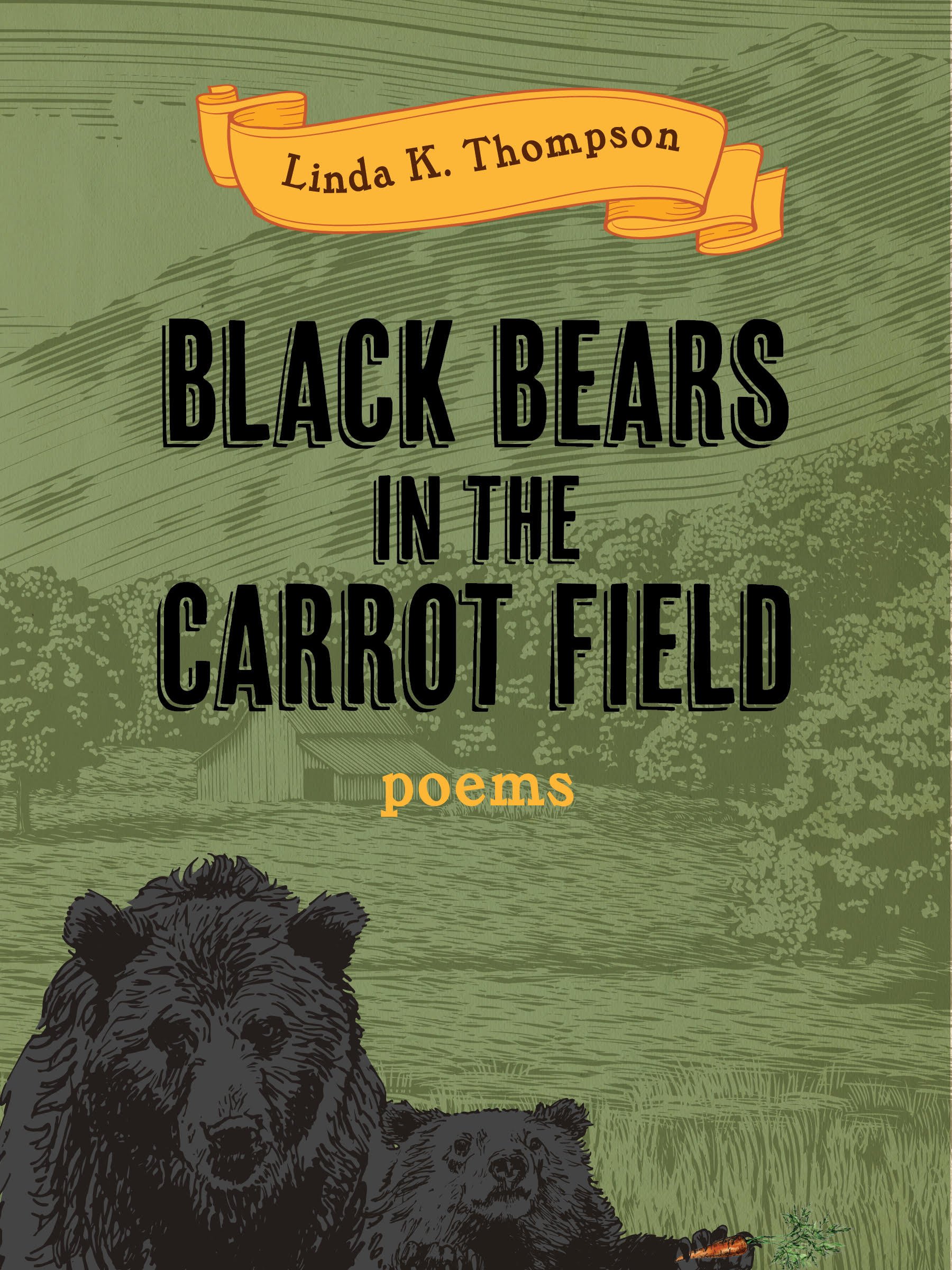

Linda K. Thompson lives in Port Alberni, and is busy tacking down her corner of the West Coast with as many words as she can muster up each day. Many of them fit into her debut collection Black Bears in the Carrot Field (Mothertongue Press, 2021).

Unpacking “Bring this Stone to the Grave”

Linda K. Thompson’s readers have come to expect her offbeat humour, her folksy narratives, and a trademark nostalgia for her Pemberton Valley childhood.

But in this short poem, Thompson’s gifts are lyric rather than narrative, poignant with awareness of death embedded in the seasonal cycles of life. Her nostalgia evokes both the beauty and the harshness of her isolated childhood landscape. Her lyrics ache with awareness of time passing, life dwindling.

It is spring, season of rebirth and fertility, but “the winds are sweeping down,” drying the pastures and fields; a hard winter has crumpled the fences. Still, the sun is returning, so are the migratory birds, and memories of trees the speaker’s mother planted.

Energy sweeps through the poem’s first two sections, firstly, with its action verbs: winds are “sweeping,” “rattling;” fences “crumple,” days are “stretching,” “inching,” the sun “dips.” Birds are “flying through the nights.” No lazy verbs here!

Secondly, the poet uses enjambment throughout these two stanzas: that is, meaning flows from line to line with little punctuation to slow it down. Except for the end-stopped first line, the first stanza is all one sentence. The second stanza is only two sentences. If we read them aloud, we are almost out of breath, echoing the sweeping winds.

Now we see the poem is in two sections, each headed with a blunt order: “Come up through the fields.” “Bring this stone.” And we realize this is not just a “nature” poem, despite its beauty, but an account of the speaker’s journey as she carries the weight of the stone, the burden of grief. Her memory is intimate and tender, the memorial stone “smooth as …Father’s old Viyellas,” evoking “the long summers” of childhood.

Its beauty, like that of the poem, “will nearly break your heart.”