REVIEWER: Wendy Donawa is grateful to live on the unceded territory of the Songhees and Esquimalt peoples, and to see the Salish Sea and the Sooke Hills from the window over her desk. Our Bodies’ Unanswered Questions is her second collection.

Poet Wendy Donawa

unpacking the poem:

Regional reviewers focus on regional poems

Reviewer Wendy Donawa unpacks a different poem every month. She examines the poem in a way she hopes is helpful for readers and other poets to understand how craft works in a particular poem, for a particular effect.

NOVEMBER 2022: rhonda ganz

The King is Old and Fat, and Moves One Square, Even in his Underwear

Childless me lunches with Yvette: she birthed the genius twins.

Five years old and playing chess, against her too

they’re competent. She has read they will have advantage

over not-chess playing twins, primed as they are

for pawn’s angled ambush, knight’s oblique

attack. Childless me, fan of the rook, his rain-slicked tower,

flips a coin, opens with a Fool’s Mate combination. Imagine that.

A war with rules—kinder than the court, kinder

than the schoolyard. Opposite the queen across a checkered board.

Are your darlings ready for the skirmish? Look for the signs: the child

asks you to show her how to play, the child knows how

to share and take turns.

I met a genius once.

He said all the pieces make the same sound

when they fall over.

Poet Rhonda Ganz not writing poems

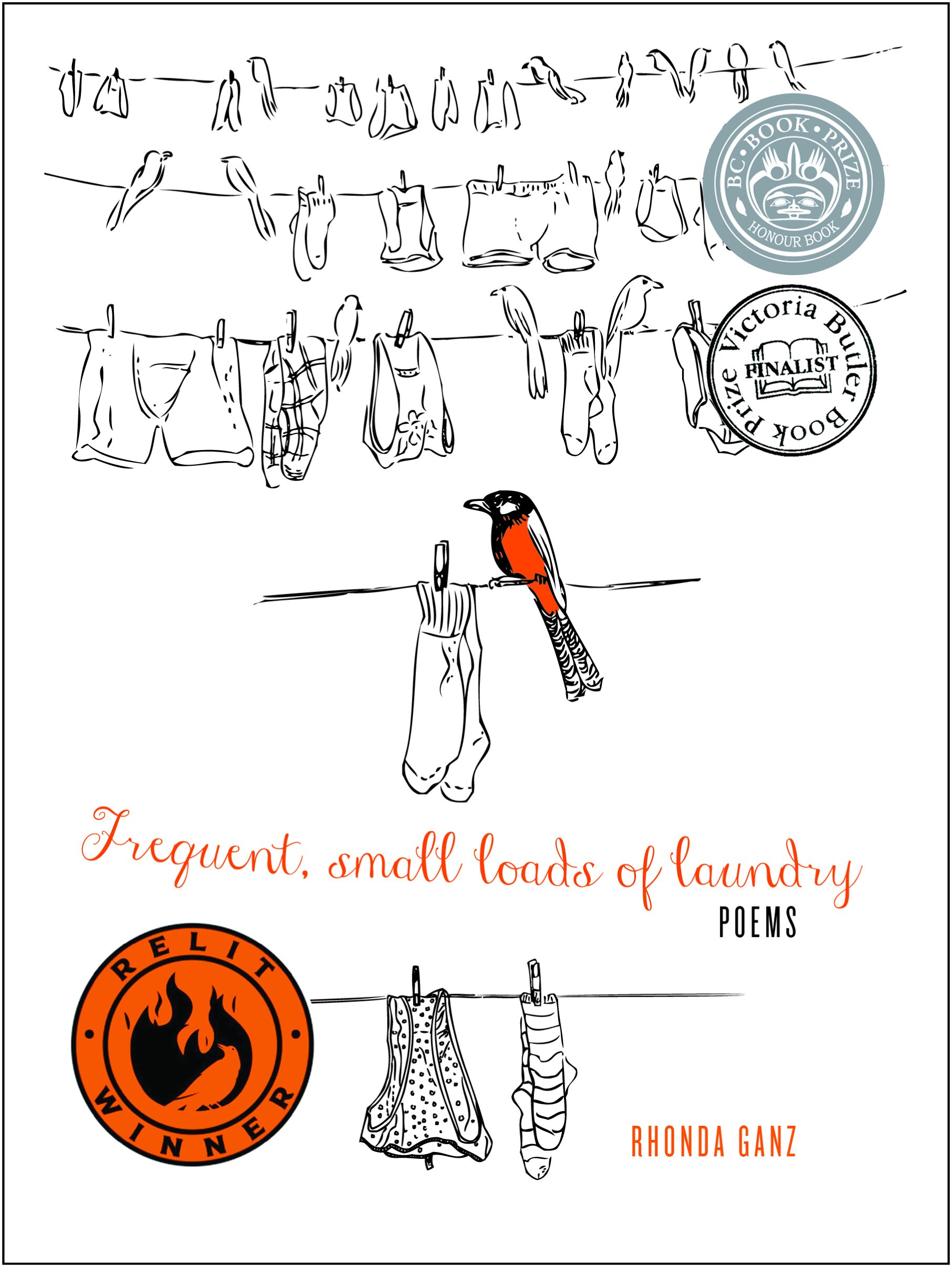

Rhonda Ganz’s Frequent, small loads of laundry (Mother Tongue, 2017, her first collection, was shortlisted for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay prize, nominated for the 2018 Victoria Butler Book Prize, and winner of the ReLit Award for poetry. Lorna Crozier writes, “What a magician of words….what sleights of narrative…If this is what laundry looks like…I want some on my line.” Arleen Pare´ finds Rhonda’s poems” “smart, sassy, quirky, scary—and funny.” The rest of us just say, “did she just say that?”

Unpacking “Sword Ferns in Spring”

Did the sly absurdity of the title stop you in your tracks? If you’re a chess player, you probably recognize the title as a mnemonic for children to learn and remember this chess move.

But is this poem essentially about chess? Rhonda Ganz’s speaker, “childless me” lunches with her friend, Yvette, mother of “genius twins.” Resentful of a comparison she is not allowed to forget, when “childless me” is repeated, she downgrades the twins’ “genius” to “competent.” She describes Yvette with sardonic humour, a helicopter parent grooming her twins for “advantage” (over other children, as Yvette’s is over other parents, and over the childless speaker).

Dark memories are implied: the speaker judges chess rules “kinder than the court” of adult manoeuvres, “kinder than the schoolyard,” and we wonder if Yvette’s high-handedness dates back to their childhood. And, is Yvette getting her darlings “ready for the skirmish,” ready for the devious chess-game of life?

Even for non-chess-playing readers, the poem’s wonderfully-named chess-moves offer compelling images that enrich the fabric of the poem: “pawn’s angled ambush, knight’s oblique/attack,” “the rook, his rain-slicked tower.” Doubtless, chess-players will recognize and interpret other meanings.

The poem’s shifting tone implicates the reader; it’s rather like eavesdropping on an unsavoury piece of gossip. The narrator wants us to see through Yvette’s pretensions. The tone of the final monosyllabic few lines is blunt: “I met a genius once.” An ironic echo that reverses the first line’s “genius.”

It takes a rare talent to juggle sly wit with the dark human impulse to control. At the poem’s end we are still laughing out loud as Ganz douses us with the cold water of the human condition: Pawns and queens joust; women battle for status and prestige; children start it all off with playground tyrannies. In the end, they’re all mortal “when they fall over.”