REVIEWER: Wendy Donawa is grateful to live on the unceded territory of the Songhees and Esquimalt peoples, and to see the Salish Sea and the Sooke Hills from the window over her desk. Our Bodies’ Unanswered Questions is her second collection.

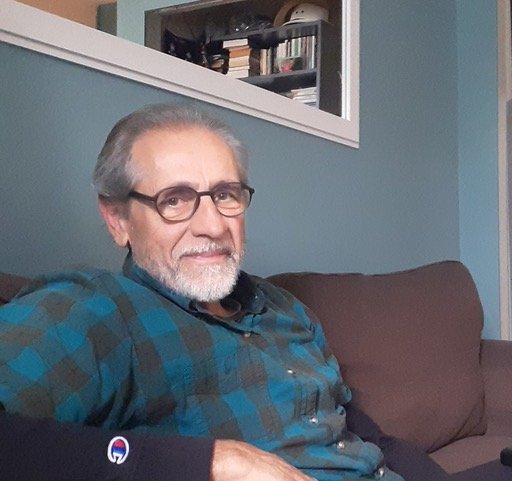

Poet Wendy Donawa

unpacking the poem:

Regional reviewers focus on regional poems

Reviewer Wendy Donawa unpacks a different poem every month. She examines the poem in a way she hopes is helpful for readers and other poets to understand how craft works in a particular poem, for a particular effect.

april 2024: stephen T. Berg

“For All That is Given”

I

Wind rushes past the reed and is transformed into sound.

The earth hums at the sign of light and calls up the evergreen.

Water rolls over rock and is given voice.

II

Moss thrives upon the fallen aspen.

Ants build beautiful cities in the trunk’s heartland.

And what the aspen knew of the sun is given over to the ground.

III

The bow is drawn across the string.

The string quickens to sing within friction of horsehair and rosin,

Filling in all the spaces between here and home.

IV

At the mouth of the cave sits the salamander.

Warm light spills in and the cool dark rock says be still.

There she balances between immense desires, perfectly moist.

Stephen T Berg’s poetry has appeared in various anthologies, including Hologram (2023), and in such publications as Rattle, Prairie Fire, Orion, Earthshine, Geez, oratorealis, Westender, and Christian Courier.

Recently he was awarded first place in poetry with Canadian Christian Communicators Association. His first chapbook, There Are No Small Moments, was published by The Rasp and The Wine (2014), and his first full-length book of poetry, Beacon, Blues and Holy Goats, was published by Aeolus House (2019). He currently resides on the ancestral lands of the Coast Salish Peoples. For more of his work visit: growmercy.org

Unpacking “For All That is Given” by Stephen T. Berg

The late, great poet Tony Hoagland suggested an intriguing frame for responding to poems. Just as several Eastern cultures consider different physical chakras as significant energy centres, so Hoagland offers three poetry chakras: imagery, diction, and rhetoric.

All four stanzas of Stephen Berg’s poems are rich in the first chakra, imagery suggesting energy and transformation. All the senses are evoked; everything is in motion: wind rushes, earth hums, and water is given voice. Human as well as natural energies abound; the musician’s artistry sings within the frictions of the physical world. Images filled with conscious and unconscious energies, this is, at first reading, an intuitive, evocative celebration of nature, and on this level it succeeds beautifully.

Reading the poem through the second diction chakra, we find added layers of subtle complexity. Diction is fueled by intellectual acumen: word choice and word-play are conscious and deliberate, precise and suggestive (the first line’s wind and reed suggest a woodwind musician, and prepare us for the later string and bow. The lyrical second line is also a description of photosynthesis). A richly energetic choice of strong verbs (rushes, hums, calls, rolls, thrives, build, quickens, spills) serve the changes and transformations of the natural and human worlds.

The third chakra, that of rhetoric , is a speaker’s formal persuasive stance, using literary and formal devices to shape language toward some assumed listener. Just as the reader is not surprised to find an environmental and social justice energies behind Berg’s response to the natural world, so it is unsurprising to find he is also a scholar of theology and philosophy.

Berg’s poem is lavish in rhetorical devices and brings us to the paradox at the heart of transformation. Wind, earth and water are transformed to alternate energies. The death and decay of the aspen brings life to the moss, “beautiful cities” to ants, and fertility to the soil. Music itself can only be produced through “friction,” but it fills “all the spaces between here and home.” The salamander is a mythic emblem of transformation, and there is something almost Biblical in the rushing wind, the “quickening”, the wording of the title, the balance of “immense desires,” in the music, cadence, and cosmic imagery of the poem. And after all this tumultuous, fertile activity, the injunction is to “be still.” A contemplative calm as we seek to balance our own immense desires.